The Orange Book isn’t a novel you pick up for bedtime reading. It’s a government publication that quietly decides whether your $5 generic pill can legally replace your $150 brand-name drug. Every time a pharmacist swaps out your brand-name medication for a cheaper version, they’re using the Orange Book as their rulebook. This isn’t guesswork. It’s science, regulation, and billions of dollars in savings - all tracked in a single, monthly-updated reference guide published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The official name is Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. But everyone calls it the Orange Book because of its bright orange cover. First published in 1980, it was created to solve a real problem: how to let generic drugs enter the market without risking patient safety. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 gave the FDA the legal power to make this happen. Before that, generic manufacturers had to repeat the same expensive clinical trials as the original drugmaker. The Orange Book changed that. Now, generics can prove they work the same way - without redoing every study.

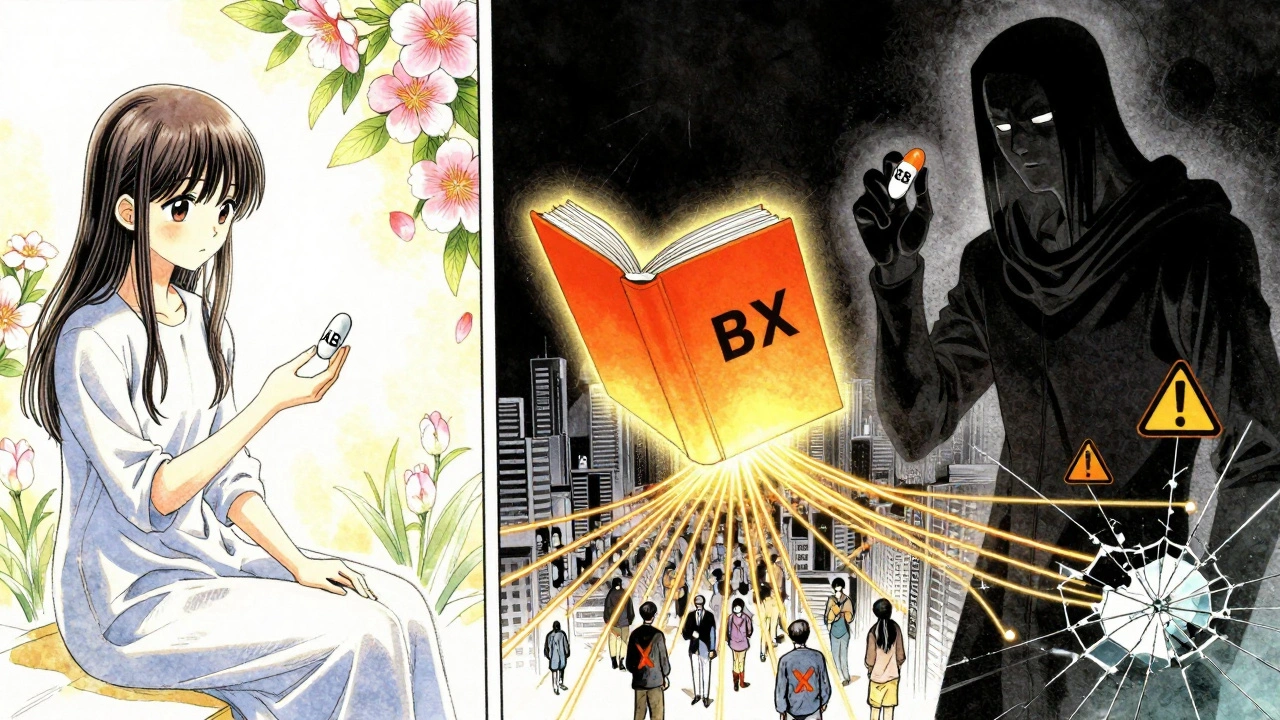

The book doesn’t just list drugs. It evaluates them. For every approved drug product, the FDA assigns a Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) code. That code tells pharmacists and insurers whether a generic can be swapped in place of the brand-name version. If a drug has an ‘AB’ code, it’s cleared for substitution. If it’s ‘BX’, it’s not. Simple, right? Not always.

For two drugs to be considered therapeutically equivalent, they must meet three strict criteria. First, they must be pharmaceutically equivalent. That means they contain the same active ingredient, in the same amount, in the same form - tablet, capsule, injection - and follow the same manufacturing standards. A 10mg lisinopril tablet from one company must match the 10mg lisinopril tablet from another in every measurable way.

Second, they must be bioequivalent. This is where things get technical. Bioequivalence means the body absorbs and processes the drug the same way. The generic must deliver the same amount of the active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. If the brand-name drug hits peak concentration in 2 hours, the generic must hit it within a narrow window - usually within 80% to 125% of that time. The FDA tests this using blood samples from healthy volunteers. If the data doesn’t match, the drug gets flagged.

Third, the FDA must officially recognize the product as safe and effective. That means it’s manufactured under Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP), labeled correctly, and approved through the right pathway - usually an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Only then does it get a TE code.

The TE code system is the heartbeat of the Orange Book. Every approved drug gets a two-letter code. The first letter tells you if it’s equivalent (A) or not (B). The second letter gives details about the type of equivalence.

‘AB’ means the drug is therapeutically equivalent with no known bioequivalence issues. This is the gold standard. If your prescription says ‘AB’, your pharmacist can swap it without asking. ‘AN’ and ‘AO’ are also ‘A’ codes - they mean the drug is equivalent, but the formulation is complex (like extended-release or inhalers), and the FDA has reviewed the data and approved substitution.

‘BX’ is a red flag. It means the FDA doesn’t have enough evidence to confirm therapeutic equivalence. This often happens with complex generics - think nasal sprays, topical creams, or injectables - where small differences in how the drug is delivered can matter. ‘BC’ and ‘BD’ codes are similar. They indicate potential bioequivalence problems. These drugs are often left as brand-only, even if a generic exists.

Pharmacists see these codes every day. But they’re not always clear. A 2023 survey found 67% of pharmacists found the TE code system ‘moderately to extremely difficult’ to interpret without training. One wrong code interpretation can lead to a denied insurance claim - or worse, a patient getting a drug that doesn’t work the same way.

The Orange Book isn’t just paperwork. It’s the reason 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics - even though those generics make up only 23% of total drug spending. Over the last decade, this system saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.67 trillion. That’s not a number. That’s millions of people who can afford their blood pressure meds, insulin, or antibiotics.

But it’s not perfect. In Q1 2022, Walgreens reported $1.2 million in rejected claims because pharmacists misread TE codes. Some states have strict substitution laws - if the Orange Book says ‘AB’, the pharmacist must substitute. Others let the prescriber block substitution. This creates confusion. One study found 78% of pharmacy technicians had seen cases where the pharmacist wasn’t sure if a generic could be swapped.

On the flip side, CVS Health built an automated system in 2021 that checks TE codes in real time. It cut substitution errors by 63% and saved $47 million a year. That’s the power of getting it right.

Pharmacists use it daily. Insurance companies use it to decide what to cover. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) use it to build formularies. State boards of pharmacy use it to write laws. The FDA itself uses it to track which generics are approved and where.

But here’s the catch: the public rarely sees it. Patients assume their generic is safe because it’s cheaper. They don’t know about TE codes. And that’s okay - as long as the system works behind the scenes. But when it doesn’t, problems arise. A patient on warfarin (a blood thinner with a narrow therapeutic index) might get a generic that’s slightly different in absorption. That small difference can cause dangerous bleeding or clots. That’s why some drugs, even if they’re ‘AB’, come with special warnings.

The FDA is updating the Orange Book. The old print version is gone. Now it’s a searchable online database, updated monthly. By mid-2024, it will include application numbers, applicant names, and drug strengths all in one place. That’s a big step forward.

But the real challenge is complexity. Inhalers, patches, injectables - these aren’t simple pills. The FDA now says the device doesn’t have to be identical, but the clinical effect must be the same. That’s harder to prove. For example, a generic inhaler might use a different propellant, but still deliver the same dose to the lungs. The FDA evaluates this case by case. It’s slow. It’s expensive. But it’s necessary.

Biosimilars - the generic version of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel - aren’t in the Orange Book yet. They’re tracked separately. But the same principles apply. The FDA is building a framework for them, and one day, the Orange Book may expand to include them too.

If you’re taking a generic drug, you can feel confident - most of them are safe and effective. The Orange Book makes sure of it. But if you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index - like lithium, digoxin, or phenytoin - ask your pharmacist. Even if it has an ‘AB’ code, your doctor might prefer you stay on the brand.

If your insurance denies a generic, check the TE code. It might be a ‘BX’ drug. That’s not a mistake - it’s the system working as intended. And if you’re a pharmacist or pharmacy tech, take the training. The NCPA offers a 4-hour course. It’s worth it. One wrong code can cost a patient their health.

The Orange Book is quiet. It doesn’t make headlines. But every day, it saves lives by making medicine affordable. It’s not perfect. But it’s the best system we have.

No. The Orange Book includes both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. Part I covers prescription drugs with therapeutic equivalence codes. Part II lists OTC drugs that aren’t covered under standard monographs. Part III includes biologics approved under Section 505, and Part IV tracks discontinued or non-marketed products. So if you’re using a generic antacid or allergy pill, the Orange Book may still apply.

Only if the generic has an ‘A’ code in the Orange Book. ‘AB’, ‘AN’, and ‘AO’ mean substitution is approved. ‘BX’, ‘BC’, or ‘BD’ mean it’s not recommended. Even if a generic is cheaper, it can’t be swapped if the FDA hasn’t confirmed therapeutic equivalence. Always check the TE code before assuming substitution is allowed.

Different manufacturers can produce generics with slightly different formulations - even if the active ingredient is the same. For example, one company’s extended-release tablet might use a different coating that changes how slowly the drug releases. If the FDA finds that difference affects absorption, it may assign a different TE code. That’s why two generics of the same drug can have different codes - one might be ‘AB’, another ‘AN’.

No. The Orange Book is a U.S.-only system. Other countries have their own methods for evaluating generic equivalence. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses a similar but separate process. Canada, Australia, and the UK each have their own databases and criteria. The Orange Book’s TE codes are not recognized internationally, though many countries look to it as a reference.

The Orange Book is updated every month. New generic approvals, changes in TE codes, and discontinued products are added or removed monthly. The FDA publishes the updated version on its website by the last business day of each month. Pharmacies and insurers rely on this monthly update to keep their systems accurate. Out-of-date information can lead to substitution errors.

No. Biosimilars - generic versions of complex biologic drugs like insulin or monoclonal antibodies - are not included in the Orange Book. They’re tracked separately under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). The FDA has a different evaluation process for them, and they’re listed in the Purple Book, not the Orange Book. However, the principles of therapeutic equivalence are similar: the biosimilar must show it works the same way as the original biologic.

Yes. Even if a drug has an ‘AB’ code, the prescriber can write ‘Dispense as Written’ or ‘Do Not Substitute’ on the prescription. This is legal in all states. Some doctors do this for patients on narrow therapeutic index drugs, or if the patient has had a bad reaction to a generic in the past. Pharmacists must honor this request, regardless of the Orange Book’s recommendation.

The FDA provides a free, searchable online version of the Orange Book on its website. You can search by brand name, generic name, active ingredient, or TE code. The database is updated monthly and includes all approved drugs with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. Many pharmacy software systems also integrate this data automatically.

Iris Carmen

9 12 25 / 22:21 PMso i just found out my generic blood pressure med is AB-coded and i never even checked lol. like, i just assumed it was fine bc it cost half. mind blown. 🤯

Shubham Mathur

10 12 25 / 10:11 AMthe orange book is the unsung hero of american healthcare and nobody talks about it. pharmacists are the real MVPs trying to decode these codes while juggling 50 prescriptions and an angry customer who wants their brand name drug for $3. this system saves billions but gets zero credit. also the FDA needs to simplify the TE codes they’re a nightmare

Noah Raines

12 12 25 / 07:13 AMmy grandma’s on warfarin and her pharmacist switched her to a generic with an AB code. she got dizzy for a week. turned out the absorption was just off enough to mess with her INR. doctors don’t tell you this stuff. just trust the orange book? nah. i’d rather pay extra than end up in the ER. 🤷♂️

Nikhil Pattni

12 12 25 / 10:58 AMyou guys are missing the real issue the orange book is outdated in its approach to complex generics like inhalers and transdermal patches. the FDA still evaluates them as if they’re simple tablets but bioequivalence for aerosols depends on particle size delivery mechanism and patient technique not just plasma concentration. the 80-125% window is meaningless for inhalers because even a 5% difference in lung deposition can change clinical outcomes. and don’t get me started on how the TE codes don’t even account for patient adherence or device usability. the system is built for 1984 not 2024. also i work at a pharma company so i know what i’m talking about 😎

Brianna Black

13 12 25 / 03:24 AMAs a former clinical pharmacist, I must say the Orange Book is a masterpiece of regulatory precision-though its implementation remains fraught with human error. The TE coding system, while elegant in theory, is often misinterpreted due to insufficient training. Moreover, the distinction between AB and AN codes is not intuitive to the average pharmacy technician, let alone the patient. One cannot overstate the importance of continuing education in this domain. I have personally witnessed adverse events stemming from misread codes. The FDA’s transition to a dynamic, searchable database is a step in the right direction, but without standardized certification for pharmacists, we remain vulnerable to systemic fragility.

precious amzy

13 12 25 / 06:46 AMHow quaint. You treat the Orange Book as if it were an oracle of pharmaceutical truth. But let us not forget: it is a bureaucratic artifact, shaped by lobbying, patent cliffs, and the commodification of human biology. The notion that ‘bioequivalence’ can be reduced to a 20% absorption window is not science-it is capitalism dressed in lab coats. The FDA does not protect patients; it facilitates cost-cutting under the guise of equivalence. And yet we genuflect before this orange tome as if it were sacred scripture. How tragically postmodern.

Morgan Tait

14 12 25 / 19:54 PMyou know the orange book is just a front right? the real reason generics are approved is because big pharma owns the FDA and they want you to buy cheap drugs so they can raise prices on the brand ones later. also the TE codes? they’re coded. AB doesn’t mean safe-it means ‘we got paid to approve this’. and don’t get me started on how the monthly updates are timed to coincide with insurance renewal cycles. you think that’s coincidence? nope. it’s control. they want you dependent on the system. wake up people. the orange book is a trap. 🕵️♂️

Chris Marel

16 12 25 / 08:47 AMas someone from nigeria where generics are often the only option, i’ve seen how this system saves lives. here, people don’t have insurance or choice-they just need the medicine to work. i’m glad the u.s. has this structure. but i also worry that when people say ‘it’s just a generic’, they forget that someone’s life depends on it being right. thank you for explaining the te codes. i didn’t know how much went into this.

Maria Elisha

17 12 25 / 19:19 PMso… this book is just a giant list of which generics you can swap? why is this even a thing? i just want my pill to work. why do i need to know all this?

Stacy Tolbert

18 12 25 / 06:47 AMi read this whole thing and i’m crying. not because it’s sad-because it’s beautiful. this invisible system keeps millions of us alive. my dad’s on insulin, my mom’s on lithium, and i used to think ‘generic’ meant ‘lesser’. now i know it means ‘carefully vetted’. thank you for writing this. i’m sharing it with my whole family.