| Date | Symptom | Severity | Activity | Duration | Notes |

|---|

Living with Hypertrophic Subaortic Stenosis means learning to balance everyday activities with a condition that narrows the pathway blood takes out of the heart. The good news? With the right toolbox-regular check‑ups, smart medicine choices, lifestyle tweaks, and timely procedures-you can keep symptoms under control and enjoy a full life.

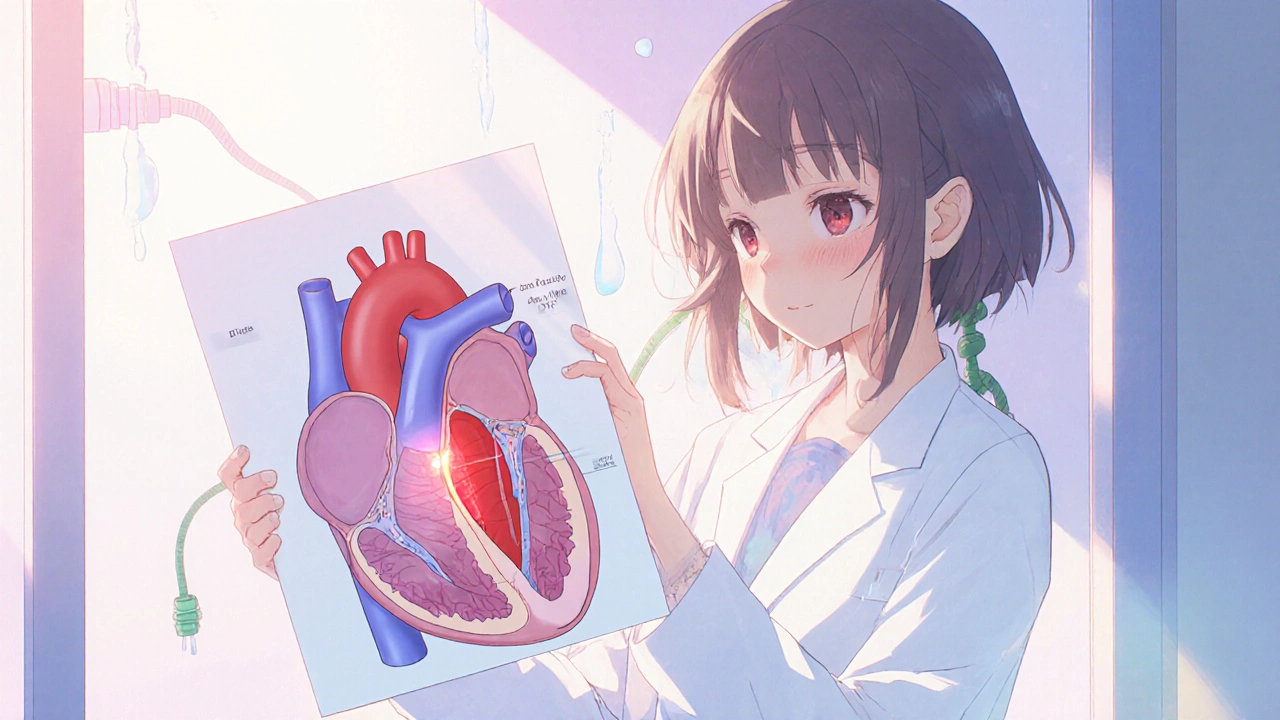

Hypertrophic Subaortic Stenosis is a type of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy where the septum (the wall between the heart’s left chambers) thickens, creating an obstruction in the left ventricular outflow tract. This narrowing forces the heart to work harder, often causing shortness of breath, chest discomfort, fainting spells, or an irregular heartbeat. The condition can be inherited, showing up in families with a history of sudden cardiac death.

When the septum bulges into the blood‑flow channel, the heart’s pump efficiency drops. Think of it like a garden hose that’s kinked in the middle; water still gets through, but you need more pressure. Your heart compensates by thickening its walls even more, which can lead to a cycle of worsening obstruction.

Doctors grade the severity using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, ranging from I (no limitation) to IV (symptoms at rest). Knowing your class helps guide treatment decisions-from lifestyle changes to invasive procedures.

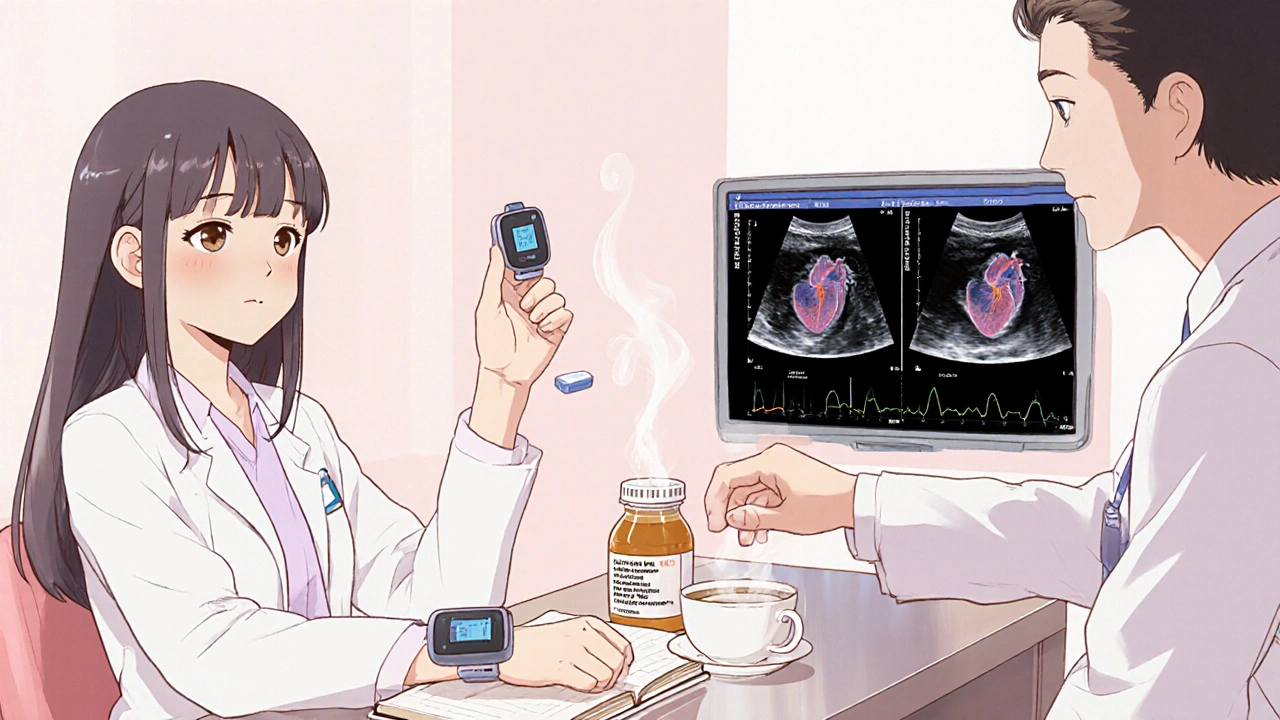

Staying ahead of HSS means regular monitoring. The gold‑standard test is the echocardiogram an ultrasound scan that shows heart wall thickness, outflow gradient, and valve function. Most patients get an echo every 6‑12 months, but if symptoms change, an earlier scan is wise.

Other tools include:

Keep a symptom diary: note breathlessness, chest pain, palpitations, and any fainting episodes. Bring this log to every cardiology visit; it helps the team adjust medication or decide on interventions.

Medications are the first line of defense when the obstruction causes noticeable symptoms. The most common class is beta‑blockers.

Beta‑blockers drugs that slow the heart rate and reduce contractility, lowering the pressure gradient across the narrowed outflow tract such as metoprolol or atenolol can relieve shortness of breath and chest discomfort. Start low, increase gradually, and monitor blood pressure and heart rate.

Other medication options include:

Always discuss dosage changes with your cardiologist. Some patients find that a combination of a low‑dose beta‑blocker and a calcium blocker balances symptom control with tolerability.

If symptoms persist despite optimal medication, it’s time to explore procedures that physically reduce the obstruction.

Surgical Septal Myectomy an open‑heart operation where the surgeon removes a portion of the thickened septum to widen the outflow tract has been the gold standard for decades. It offers immediate relief and long‑term survival benefits, especially for younger patients with severe gradients (often >50 mmHg).

For those who prefer a less invasive route, Alcohol Septal Ablation a catheter‑based technique that injects a small amount of alcohol into a targeted septal artery, causing a controlled scar that thins the obstructive tissue can achieve similar gradient reductions. It’s usually reserved for patients who are higher surgical risks or who have anatomy amenable to the approach.

| Aspect | Surgical Myectomy | Alcohol Septal Ablation |

|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Open‑heart surgery (sternal incision) | Minimally invasive catheter procedure |

| Hospital stay | 5‑7 days | 1‑2 days |

| Immediate gradient reduction | Usually >70% reduction | 60‑70% reduction, may need repeat |

| Long‑term durability | Excellent, decades of follow‑up data | Good, but rare late‑onset gradients |

| Risk of heart block | 5‑10% (may need permanent pacemaker) | 10‑15% (higher pacemaker need) |

Both procedures have excellent outcomes when performed at experienced centers. Talk with your cardiologist about your age, anatomy, and personal preferences to decide which path fits best.

Beyond medical care, daily habits make a huge difference.

Regular, moderate‑intensity aerobic exercise improves heart efficiency without overloading the outflow tract. Good options include brisk walking, stationary cycling, and swimming. Aim for 150 minutes a week, split into 30‑minute sessions.

Avoid high‑intensity bursts (e.g., sprinting, heavy weightlifting) that can trigger a sudden rise in obstruction pressure. If you’re unsure, a cardiac rehabilitation program can tailor a safe exercise plan.

Maintain a healthy weight to reduce the heart’s workload. Focus on a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and low in saturated fat. Limit excessive caffeine and energy drinks, as they can raise heart rate and provoke arrhythmias.

Staying hydrated helps keep blood volume steady, which can ease symptoms. However, if you have concurrent heart failure, your doctor may advise a sodium‑restricted diet (<2 g per day) to avoid fluid overload.

Living with a chronic heart condition can feel isolating. Feeling anxious about symptoms is normal, but chronic stress can raise blood pressure and worsen outflow gradients. Techniques like mindfulness, deep‑breathing exercises, and gentle yoga can lower stress hormones.

If you notice persistent low mood, consider talking to a mental‑health professional. Peer support groups-online or in‑person-offer shared experiences and practical tips.

Because HSS often runs in families, first‑degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) should be screened even if they feel fine. A simple echo can reveal early thickening before symptoms appear.

When a pathogenic mutation is identified, genetic testing DNA analysis that looks for known mutations linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can pinpoint the exact gene involved. Knowing the mutation helps guide surveillance for relatives and may inform future therapies.

Patients with a history of ventricular arrhythmias or a very high risk of sudden cardiac death may benefit from an Implantable Cardioverter‑Defibrillator (ICD) a small device placed under the skin that monitors heart rhythm and delivers a shock if a dangerous rhythm is detected. The decision is based on factors like family history, unexplained syncope, and the extent of wall thickness (usually >30 mm).

ICD implantation involves a minor surgery, and most patients return to normal activities within a few weeks. Regular device checks (in‑clinic or remote) ensure the system works correctly.

This routine blends medication adherence, safe exercise, nutrition, and symptom tracking-four pillars of effective HSS management.

Call emergency services or go to the nearest hospital if you experience any of the following:

Prompt treatment can prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Here are a few reliable places to find more information and community:

Connecting with others who understand the day‑to‑day challenges can reduce anxiety and give practical ideas you might not have considered.

Symptoms usually flare when the heart has to pump harder, such as during exercise, emotional stress, or after a big meal. The thickened septum narrows the outflow tract, so anything that increases heart rate or blood volume can make the blockage feel worse.

Yes, but plan ahead. Carry a copy of your latest echocardiogram, know the nearest hospital with cardiac services, and keep medications with you. Avoid very high altitudes unless cleared by your cardiologist.

For many seniors, ablation is a viable alternative to open‑heart surgery because it avoids a sternotomy and has a shorter recovery. The main concerns are a slightly higher risk of heart block and the need for careful imaging to target the right artery.

If you’re stable and symptom‑free, an echo every 12 months is common. Any change in symptoms or medication should trigger an earlier scan.

Maintaining a regular, moderate exercise routine, keeping a healthy weight, limiting caffeine, and managing stress are the top three changes that most patients report as helpful.

Dana Yonce

21 10 25 / 15:52 PMGreat guide! 😊

Lolita Gaela

31 10 25 / 14:52 PMThe article aptly delineates the hemodynamic implications of septal hypertrophy, emphasizing the utility of serial transthoracic echocardiography for gradient quantification. It also judiciously references the NYHA functional classification as a therapeutic decision matrix. Beta‑blockers, particularly metoprolol succinate, are highlighted for their negative chronotropic effect, which mitigates outflow obstruction. Calcium channel antagonists such as verapamil serve as adjuncts in patients intolerant to beta‑blockade, owing to their lusitropic properties. For refractory cases, the discussion of septal myectomy versus alcohol septal ablation is comprehensive, noting the superiority of surgical resection in younger cohorts with pronounced gradients.

Giusto Madison

10 11 25 / 14:52 PMAlright, let me break this down for anyone still stuck on the basics. First off, you need to own your medication schedule like it’s a part‑time job – take that beta‑blocker with breakfast, no exceptions, because missing a dose throws your heart back into overdrive. Second, the symptom diary isn’t a novelty item; log every wheeze, every flutter, even the weird light‑headed moments after a big meal – those tiny data points are what guide dosage tweaks. Third, exercise isn’t a free‑for‑all; stick to steady‑state cardio – think brisk walks or a stationary bike at a pace where you can still hold a conversation without gasping. Fourth, avoid any high‑intensity bursts – sprinting, heavy deadlifts, or competitive tennis – they spike the LVOT gradient and can precipitate syncope. Fifth, hydration is key but don’t overdo salty snacks unless your cardiologist tells you otherwise, because excess sodium can exacerbate any underlying heart failure component. Sixth, schedule that echo at least annually, or sooner if you notice any new chest pressure or dizziness – early detection of gradient progression can save you from an emergency surgery. Seventh, if you’re eligible for a septal myectomy, push for a high‑volume center; the outcomes there are far superior to low‑volume hospitals. Eighth, consider alcohol septal ablation only if you’re a poor surgical candidate – the risk of complete heart block is higher, and you might end up with a pacemaker you didn’t plan for. Ninth, if you have an ICD, remember the remote monitoring feature – it’s not just a gimmick; it can catch arrhythmias before they become life‑threatening. Tenth, keep your stress levels in check – chronic cortisol spikes can worsen hypertrophy, so adopt some mindfulness or breathing exercises daily. Eleventh, nutrition matters: lean proteins, plenty of leafy greens, and limited caffeine – energy drinks are a no‑go because they can trigger arrhythmias. Twelfth, watch your weight – every extra pound forces your heart to pump harder against that narrowed outflow. Thirteenth, be proactive about family screening; genetic testing can pinpoint at‑risk relatives before they develop symptoms. Fourteenth, stay educated – follow reputable cardiology podcasts or journals so you’re not blindsided by new guidelines. Lastly, never ignore red‑flag symptoms like sudden severe chest pain, fainting spells, or rapid worsening shortness of breath – call EMS immediately. Follow this playbook and you’ll stay ahead of HSS rather than constantly reacting to it.

Devendra Tripathi

20 11 25 / 14:52 PMWhile the enthusiasm is appreciated, let’s not pretend that lifestyle tweaks alone will magically dissolve a 2‑centimeter septal bulge. The reality is that many patients will still end up needing an invasive procedure despite strict adherence to exercise and diet. Moreover, the claim that “stress management can shrink the septum” is pure hype; cortisol can affect symptoms but it doesn’t reverse structural hypertrophy. If you’re banking on medication titration to replace surgery, you’re gambling with potentially fatal obstruction gradients. In short, the article underplays the inevitability of procedural intervention for a sizable portion of the cohort.

Vivian Annastasia

30 11 25 / 14:52 PMOh sure, because everyone has endless time to monitor their heart like it’s a stock portfolio. And let’s not forget the joy of adding another “must‑avoid” list to your already packed schedule. Guess we’ll all just love living in a world where caffeine is the devil.

John Price

10 12 25 / 14:52 PMSounds solid.

Nick M

20 12 25 / 14:52 PMHonestly, all these guidelines feel like a distraction from the fact that big pharma pushes beta‑blockers to keep us dependent. You hear the same echo schedule every year, but nobody mentions the hidden fees in those “advanced imaging” packages. It’s a well‑orchestrated loop to keep the industry humming.

eric smith

30 12 25 / 14:52 PMRight, because the only way to truly understand HSS is to memorize every nuance of gradient percentages – obviously you’re all missing the point. If you’re not consulting the latest meta‑analysis from the top five journals, you’re basically guessing.