Typically occurs 6-72 hours after consuming contaminated food

Symptoms usually appear within minutes to 2 hours

Ever wondered why some people develop new food sensitivities after a bout of food poisoning? The link between salmonellosis and food allergies is real, and understanding it can help you protect yourself and your family.

When you hear about Salmonellosis is a bacterial infection caused by Salmonella that typically attacks the intestines. Common sources include undercooked poultry, eggs, and contaminated produce. Symptoms usually appear 6‑72hours after ingestion and can include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, fever, and sometimes headache.

Diagnosis often relies on a stool culture that isolates the Salmonella organism, confirming the infection.

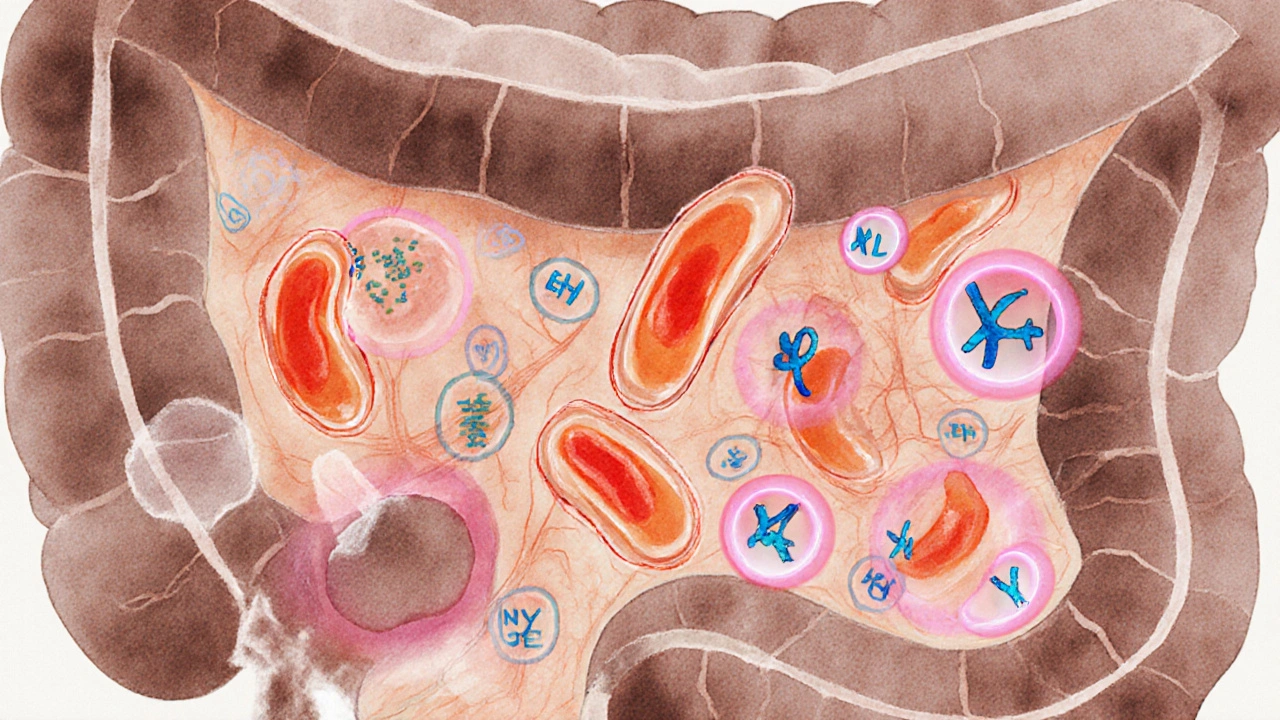

A food allergy is an abnormal immune reaction to a specific food protein, mediated primarily by Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. When a sensitized person eats the trigger food, IgE on mast cells recognises it, releasing histamine and other chemicals that cause itching, swelling, hives, respiratory distress, or even anaphylaxis.

Allergy testing-skin prick or serum IgE measurement-helps pinpoint the culprit foods.

At first glance, an infection and an allergy seem unrelated. However, research shows that a severe Salmonellosis episode can disrupt the gut’s normal barrier and immune balance, setting the stage for two possible outcomes:

Both pathways involve the immune system and its complex communication with the gut microbiome.

The gut lining is packed with immune cells that keep harmless foods from triggering a response. During a Salmonellosis infection, the following cascade often occurs:

In people with a pre‑existing dysbiotic gut (low diversity of beneficial bacteria), the odds of this cascade completing are higher. Probiotic depletion, often seen after antibiotics used to treat severe salmonellosis, removes the natural checks on inflammation.

Not everyone who gets salmonellosis will develop a food allergy. Certain factors increase the likelihood:

In a 2023 Australian cohort study of 1,200 salmonellosis patients, 8% reported new‑onset food allergy within six months, compared with 2% in a matched control group.

Whether you’re trying to avoid infection or minimise the allergy risk afterward, these practical steps can help.

Should a true food allergy develop, avoid the trigger completely, carry an antihistamine for mild reactions, and keep an epinephrine auto‑injector on hand for severe cases.

| Feature | Salmonellosis | Food Allergy |

|---|---|---|

| Onset after exposure | 6‑72hours | Minutes to 2hours |

| Typical gastrointestinal signs | Profuse diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, fever | Rare; may include stomach upset |

| Skin manifestations | Occasional rash (rare) | Hives, itching, angio‑edema |

| Respiratory involvement | Uncommon | Wheezing, throat tightness |

| Duration | Usually 4‑7days (can be longer if severe) | Persistent for life unless desensitised |

It’s possible, but not guaranteed. Studies suggest 5‑10% of severe cases lead to lasting IgE sensitisation. Early intervention with probiotics and monitoring can reduce the chance.

Most new allergies appear within 2‑8weeks post‑infection, but delayed reactions up to six months have been reported. Keep a diary of any unusual skin, respiratory, or gastrointestinal signs.

Broad‑spectrum antibiotics can wipe out beneficial gut bacteria, weakening the barrier that protects against sensitisation. Using targeted antibiotics when possible and adding probiotics afterward can help mitigate this risk.

Only under medical supervision. An allergist can perform a graded oral food challenge to confirm whether an IgE‑mediated allergy exists.

Yes. Children’s gut barriers are still developing, making them more vulnerable to bacterial breaches and subsequent sensitisation.

A diverse microbiome produces short‑chain fatty acids that reinforce the intestinal lining and modulate immune responses toward tolerance. Disruption by infection or antibiotics removes this protection, allowing allergens to slip through.

Vaccines exist for certain livestock strains but not for the broad range of human‑pathogenic Salmonella serotypes. Prevention relies on food safety and hygiene.

Understanding the hidden link between infection and allergy equips you to act fast, keep your gut healthy, and avoid a lifetime of unnecessary dietary restrictions.

Kimberly Dierkhising

8 10 25 / 19:03 PMThe gut‑immune axis is a sophisticated communication network that can be hijacked by enteric pathogens. When Salmonella breaches the epithelial barrier, it triggers a cascade of pro‑inflammatory cytokines such as IL‑6, TNF‑α, and IL‑1β. This cytokine milieu skews naïve T‑cells toward a Th2 phenotype, which is the hallmark of IgE‑mediated allergic sensitisation. In parallel, the disruption of tight junctions allows luminal food proteins to access the lamina propria, where antigen‑presenting cells can process them. Dendritic cells then present these novel peptide epitopes to helper T cells, potentially priming B cells to class‑switch to IgE. Once IgE coats mast cells, subsequent exposure to even trace amounts of the same protein can provoke degranulation, histamine release, and the clinical picture of a food allergy. Clinical studies have reported that up to ten percent of severe salmonellosis cases develop new‑onset IgE sensitisation within weeks. The risk is amplified in individuals with pre‑existing atopic tendencies, such as eczema or allergic rhinitis. Antibiotic therapy, while life‑saving, can decimate commensal Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria, further compromising barrier integrity. Probiotic reconstitution with strains like L. rhamnosus has been shown to restore short‑chain fatty acid production, bolstering epithelial repair. From a preventive standpoint, rigorous food safety-cooking poultry to 75 °C, avoiding raw eggs, and washing produce-remains the first line of defense. Post‑infection, a symptom diary spanning at least a month can help clinicians distinguish lingering infection‑related rash from genuine allergic urticaria. If hives, angio‑edema, or respiratory symptoms arise, prompt referral for skin‑prick testing or serum‑specific IgE is advisable. In cases where an allergy is confirmed, strict avoidance of the trigger, coupled with an epinephrine autoinjector for anaphylaxis risk, is standard care. Ultimately, maintaining a diverse gut microbiome through diet, judicious antibiotic use, and targeted probiotics may reduce the probability that a bacterial insult seeds a lifelong food allergy.

Rich Martin

9 10 25 / 06:43 AMListen up, the gut barrier isn’t a rubber stamp for any protein you chew on after a Salmonella flare‑up. If the bacteria tear up your tight junctions, you’re basically opening the floodgates for allergens to crash the party. That’s why you see hives and wheeze popping up weeks later – your immune system finally gets the memo. Bottom line: don’t shrug it off, get checked.

Dustin Richards

9 10 25 / 18:23 PMIn plain terms, a severe salmonella infection can damage the lining of your intestines. That damage lets food proteins slip through to immune cells, which may start making IgE antibodies. If that happens, you could develop a true food allergy after the infection clears. It’s a good idea to watch for skin or breathing issues in the weeks after recovery.

Vivian Yeong

10 10 25 / 06:03 AMThe article covers the mechanistic link well, but it could benefit from more emphasis on the role of gut microbiome diversity. A brief mention of dietary fibers as pre‑biotics would round out the preventive advice.

suresh mishra

10 10 25 / 17:43 PMProbiotics after antibiotics can help restore gut balance.

Reynolds Boone

11 10 25 / 05:23 AMI’ve seen a buddy get sick from undercooked chicken, and a month later he started breaking out in hives whenever he ate peanut butter. He was shocked to learn it could be linked to the infection. Got him to an allergist, and now he’s managing it with avoidance and an epi‑pen.

leo dwi putra

11 10 25 / 17:03 PMPicture this: you’ve just survived a nasty bout of salmonella, feeling like a superhero after the binge‑purge of antibiotics, and then-bam!-your nose starts itching like it’s auditioning for a sneeze contest. It’s like your gut threw a wild party, invited the wrong guests, and left the door wide open for allergens. The whole scene is a chaotic mash‑up of inflammation, barrier breach, and immune over‑reaction-pure drama in your digestive tract.

Krista Evans

12 10 25 / 04:43 AMThat’s a vivid way to put it, and it really hits home. The key takeaway is to keep the gut’s “door policy” strict with probiotics and good hygiene, so those unwanted party crashers stay out.

Mike Gilmer2

12 10 25 / 16:23 PMWhoa, the cascade from bacteria to allergy is like watching a soap opera where every character suddenly decides to become a villain. First, the pathogen smashes the gut wall, then the immune system throws a tantrum, and finally you’re left with a lifelong food restriction-talk about a plot twist!

Alexia Rozendo

13 10 25 / 04:03 AMSure, because the next thing you know, your sandwich will be the cause of a global conspiracy to control the microbiome. Grab your tinfoil hat and your probiotic pills, folks.

Drew Burgy

13 10 25 / 15:43 PMFunny how the “big pharma” narrative forgets that the real puppet masters are the salmonella bacteria, slipping secret messages through our gut lining to program us for lifelong allergies. Maybe it’s time we start questioning why we’re so quick to trust vaccines over natural gut resilience.